This is my first time publishing annual predictions. The objective is simple. It is to be useful. That means surfacing insights without the noise, in a way that reframes problems and catalyzes better conversations. These predictions are less about what should happen in Hawaiʻi in 2026, as much as I’d like that, and more about what’s likely and possible. They also tend to say the quiet part, out loud.

2026 Predictions

No. 1: Hawaiʻi’s Systems Get Exposed from the Outside In

No. 2: More Restaurants Close; Better Ones Open

No. 3: Entrepreneurship Still Belongs to the Exceptions

No. 4: Philanthropy Faces More Watchdog Pressure

No. 5: Kamehameha Schools Has an Old Is New Again Moment

No. 6: Short Term Rental Owners Begin to Blink

No. 7: DPP Is Hawaiʻi’s Economic Chokepoint

No. 1

Hawaiʻi Systems Get Exposed from the Outside In

Hawaiʻi has tremendous grit, intelligence, talent, and goodwill; it also has an extreme allergy to friction. (Two things can be true.)

It is a consensus-driven culture: highly diplomatic, deeply relationship aware. The reward is stability over outcomes, inputs over outputs. This tradeoff is masked and preserved often by an appearance of progress, real or not. What results is a reluctance to disrupt existing models and power structures. By design, the system filters out the conditions for reform, like political will and agency. This makes things, in large part, uniquely and carefully insulated. Or, so we think.

Over time, Hawaiʻi has built an impenetrable (and impressive) armor for quick and structural change across all sectors. Decisions that require speed, accountability, or discomfort are deferred. Committees replace courage and delay masquerades as diligence. Therapists would call this conflict-avoidant. That approach can work when an economy is more forgiving. That era is over. When an economy loses slack, systems snap.

This is exactly why I’m optimistic.

The predictions for 2026 are about what gets exposed and what will become impossible to ignore across industries. Legacy systems built on deference, opacity, and inertia will be stress-tested by forces they don’t control. Foundational cracks will surface. This coming year will reveal which institutions are willing to reform. Ready or not.

This will not be the year everything is figured out or long-standing issues are suddenly “fixed”. Turnarounds do not work that way. Change rarely comes from within legacy power structures or the behaviors that sustained them. Reform happens when maintaining the status quo, once exposed, becomes more expensive than fixing it.

In 2026, look for courage to emerge from the constraints of external pressures. Then, watch for who is willing to absorb the cost of change and then remedy miscalibrations of the past.

No. 2

More Restaurants Close; Better Ones Open in 2026

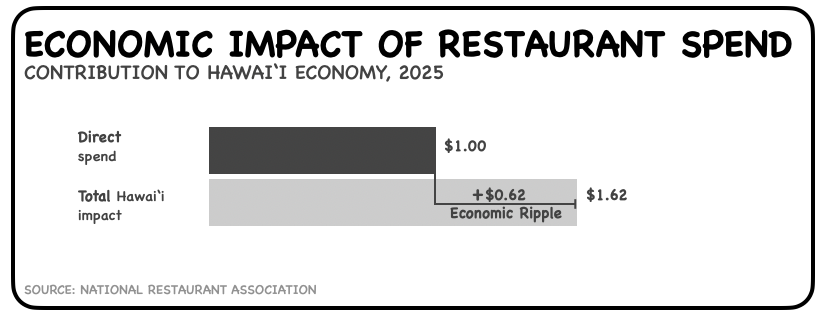

Hawaiʻi has 90,000 restaurant jobs (almost 15% of our workforce). Money spent at restaurants is a powerful economic multiplier: $1.00 spent contributes to $1.62 to the state economy. That’s real impact.

Hawaiʻi restaurants also benefit from an X-factor of nostalgia. (The memories, place, and sentiments have long substituted for margin discipline, labor stability, and operational rigor.) That safety net no longer holds, though, as external forces, like a minimum wage bump, apply pressure. This is a good thing.

The 2026 mandated $2.00 minimum wage hike, to most restaurateurs’ and owners’ chagrin, feels like an ambush. The gripes are predictable. More threats of closures, layoffs, and reduced hours. Yes, lists of restaurants closing are painful to see. But, the minimum wage mandate exposes what’s already not sustainable. Many of these restaurants that close are zombies to begin with, floating on cheaper labor and hope; restaurant economics are falling apart, and ready to be born again.

Ten years ago, I led a food and hospitality company on the east coast supporting neighborhood restaurant groups to combat the erosion of (then) traditional restaurant margins. Restaurateurs were outraged with the launch of UberEats; consumers wanted more fast casual, i.e. Chipotle. What happened when “outside forces” threatened the models? The best operators adapted and grew food empires. Landlords and suppliers reassessed. Consumers did too. It’s how healthy markets work.

What is evolving today is a vertically-integrated approach to feeding people, and with more partnership plays. (Again, a very good thing.) Foodland opened Eleven, et al, Mahi‘ai Table, and Redfish as part of their broader model; Chef Jason Peel of the now-closed Nami Kaze is revamping Diamond Head Market & Grill; Asato Family Shop is expanding with a posh dessert bar in the King & Queen’s store; Farmlink, who moved from restaurant supplier (B2B) to consumer delivery (DTC) during COVID, now partners with ‘ili‘ili Cash & Carry for a joint take out spot and retail grocer (B2C).

So, for the beloved restaurants that close (nothing lasts forever), they’ll be missed. Staff will ultimately be cycled into better models of employment and take lessons learned with them. Do we really want old models that rely on payouts of sub-poverty, sub-ALICE wages? (That’s rhetorical.) The goal should be good food, good jobs, fair wages.

Eat your values in 2026. Spend your money at places that figured this out as more do.

No. 3

Entrepreneurship Still Belongs to the Exceptions

Living in Hawaiʻi is its own stress test, especially for business, innovation and creative entrepreneurs. By most accounts, Hawaiʻi is one of the most expensive states, with the highest rent- and mortgage-burdened households, rising healthcare premiums, and virtually no safety net for early-stage risk. Layer onto that one of the lowest-ranked and least diverse innovation economies in the U.S., and the outcome is predictable. Even compared to other tourist-driven, extractive recreational economies, we are…lacking.

Hawaiʻi is not short on ideas or talent. We never built a system-level investment, a would-be viable path for a scalable, high-growth company to emerge and recycle capital, talent, and experience back into the ecosystem. In an outsized way. As a result, very few businesses reach scale without being exceptions; high-growth founders rarely get to the point where they can send checks to the next generation and keep building. We have yet to create meaningful interventions, pathways, or economic conditions that prioritize a diverse economy. (We know this intuitively and definitively.)

Last year our local venture group handed out an “intrapreneur” award…to a bank employee, as it often does. (I’m sure this person is excellent at their job.) But this kind of recognition tells you everything about the fabric of early-stage building. It regresses toward safety and incumbency and not risk, nor new value creation. Hawaiʻi’s ecosystem, largely, is designed to filter out and sideline early-stage entrepreneurs quietly. And when that happens, durable, locally anchored impact weakens. We feel it.

The clearest bright spots are emerging outside the traditional economic development ecosystem entirely. Creators are opting out. They earn globally, build audiences directly, and don’t require permission from local gatekeepers. They control distribution, own their narrative, and create optionality beyond Hawaiʻi’s capital constraints. Many are multi-threat talents and exceptional because they learned to bypass systems that were never built to support them anyway.

Jamie O’Brien may be the King of Pipeline, but his real leverage comes from the 1.3 million subscribers who have watched him surf, work, and build in public for over a decade (and now, have a baby, too). In 2026, he launches Funday Surf with boards, apparel, and gear. It will be an “overnight success” built on years of audience trust and distribution ownership. Shar Tuiasoa, aka Punky Aloha, followed a similar arc, turning design talents into global reach: a Disney partnership, a two-book deal with HarperCollins, and clients including Apple, Target, and Amazon. (And Bretman Rock, another content creator, who came back home.)

Their success can feel almost heroic, but it’s also diagnostic. Creators who combine craft, audience, and distribution seem to outperform Hawaiʻi’s traditional economic development models, not because they are favored by the system, but because they learned to work around them. In 2026, look for more Jamie O’Briens and Punky Alohas to emerge. The system will not suddenly change, but the most capable talent now has relatively new and more proven distribution models to force the issue.

No. 4

Philanthropy Faces More Watchdog Pressure

Philanthropy has enjoyed a powerful asset: the benefit of the doubt. For decades, charitable giving has often been a proxy for civic virtue. This belief continues to be stress-tested, as outcomes drift further and further from narratives.

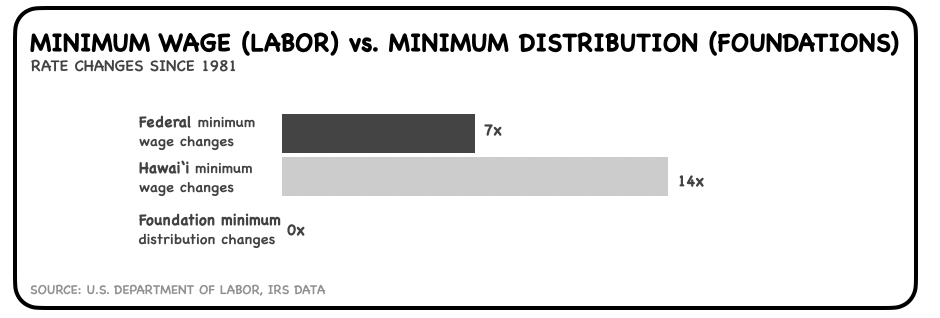

Here’s a simple comparison. Minimum wage laws have changed repeatedly since 1981, seven (7) times at a federal level and fourteen (14) times in Hawaiʻi. But in that same timespan, rules governing private foundation distributions, via the IRS, have been amended…zero. Zero times.

The minimum distribution rule (MDR), aka the 5% payout rule, unchanged for fifty years, reflects a not-so-open-secret of what the system was designed to protect, not what today’s problems require. It’s a visible mismatch. Assets can compound indefinitely, and a foundation can remain comfortably compliant—a very low bar—by distributing the minimum (especially when qualifying expenses are included). Meanwhile, across the U.S., endowments sit on roughly $1.5 trillion (read: $1,500,000,000,000) in dry powder that is, by design, not fully mobilized in the communities that need it most.

This matters in Hawaiʻi because it’s a clean example of what we’ve chosen to quietly freeze rather than modernize, and who benefits from that quiet. We live in an economy where labor is asked to adjust to reality, but capital is not.

Which brings me to a recent Civil Beat story. A reporter called the owner of a derelict Waikīkī property, once home to about ten businesses, now vacant for eight years. The article reveals: the property owner is also one of Hawaiʻi’s leading local philanthropists, tied to the No. 2 most active private family foundations. By many accounts, they’ve done real good.

The foundation reports roughly $182M in fair market value of assets on its IRS 990 form (2024) and disburses around the IRS-required minimum of 5% annually (including qualifying expenses), about $7M annually. Separately, the family controls a well-known private business generating roughly $250M–$300M in revenue. When reached for comment about the Waikīkī property, the owner reportedly agreed: it’s an “eyesore”. It’s also, he said, too expensive to redevelop. Eek.

This is a governance story. Our biggest philanthropic lever should come from local foundations. Many stop at the 5% minimum because the system tells them that’s what “responsible” looks like; it’s the consensus approach. And, it's compliance theater: meet the legal requirement, issue the press release, move on. It’s also no-longer best-practice. Spend down the endowments to solve problems of today.

In 2026, expect the traditional posture to be challenged more openly and not by insiders (boards, traditional nonprofit consultants, etc.), but by journalists and watchdogs willing to connect the dots of charitable branding to real-world outcomes. Inputs to outputs. Philanthropy will not self-correct here.

My prediction: that Waikīkī property will be transferred into the foundation and converted into a park or community space in the next twelve months, if not sold. More importantly, there will be more pointed, surgical reporting like this: call, verify, print. The facts. These stories will force public accountability and erode the idea that philanthropy, as it was designed 50 years ago, can no longer whitewash neglect of the community.

Our problems are too big to go small.

No. 5

Kamehameha Schools Has an Old Is New Again Moment

Kamehameha Schools (KS) is facing a tragedy of a lawsuit that may have even been avoidable if KS had been tuition-free. Instead, the education for many Hawaiian students is now at risk despite consensus from governors, trustee candidates, and the school to drive a tuition-free mandate through the courts (part of the stipulations of the trust). If everyone agrees that it should be tuition-free, why did it take this nefarious outside force to justify this move?

KS holds a $15 billion endowment, yet still charges families roughly $6,000 per student each year. Eliminating tuition (per student) would effectively add roughly 10% back to a family’s median household income. That kind of relief compounds. It creates room to start businesses, pay for caregiving, take a vacation, or simply stabilize a family’s footing. KS has the opportunity to treat investment in Hawaiian families as its true core responsibility. By doing so, this helps create the generational wealth needed to keep more Hawaiians home.

Today, foundations across the country are using their assets, in addition to doling out cash, to seed the conditions needed for community to thrive. Major foundations that ultimately delay leveraging endowments will shed moral authority over time. KS could go one step further than tuition-free and use that endowment to leverage workforce housing for their own educators and families (start there), or to subsidize more farmers and local food production that makes a large dent beyond what’s happening now.

This is the year the KS leadership steps out to serve those that they have been entrusted to serve: Hawaiian students and families. KS can show the world what’s possible as a reaction to this lawsuit.

No. 6

Short Term Rental Owners Begin to Blink

An economy in which kamaʻāina cannot afford to live while non-residents extract value from housing is inherently unstable, and frankly, feels hopeless for younger generations. What we’re seeing now around the Minatoya List is not just an important legal fight, it’s a market signal and a beacon of hope. Lawsuits introduce uncertainty; uncertainty introduces risk. When risk rises, markets respond.

By pushing litigation deeper into the short-term rental (STR) landscape, Minatoya supporters are injecting extrinsic risk into what had been treated as a predictable financial asset (for them). That risk will be priced in. As enforceability, zoning, and future cash flows become less certain, the valuation of homes used primarily as STRs will soften at the margin. Many non-local owners, who have already benefited from years of appreciation and strong yields due to the lack of political will, will decide not to stomach the potential downside. When uncertainty overwhelms confidence, capital can fly out. No one wants to be the last domino either.

Hawaiʻi never had a head start STR strategy to combat Airbnb early or meaningfully. No market did. The tech startup scaled and reshaped housing economics before regulators could respond. Had policymakers known just how lucrative an asset class that STRs would become—Airbnb generating roughly $1.4 million in revenue per employee vs. about $160,000 per employee at Marriott—they might have asked the obvious question sooner: how? The answer lies in structure.

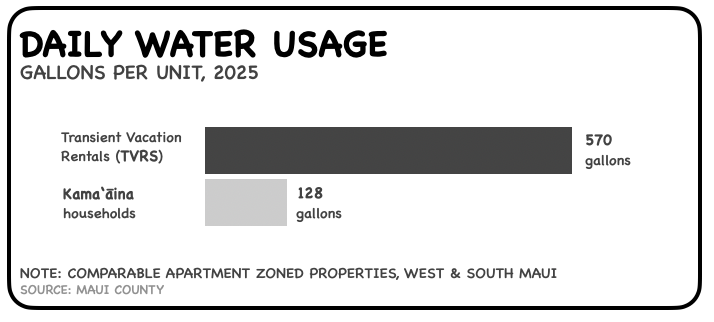

STRs became a financial instrument that captures yield and appreciation while exporting risk to community. Afterall, roughly 94% of STR properties targeted on the Minatoya list are owned by non-Maui residents. Even water usage among STR is 5x kamaʻāina usage. What? STR privatizes upside while communities absorb infrastructure strain, congestion, and displacement. Housing morphed into an investment vehicle first, shelter second.

Durable, local economies require residents. People who live where they work. People who pay local dentists and barbers, eat at neighborhood restaurants, enroll their kids in sports leagues, and spend money on birthday parties and school fundraisers.

Homes were never intended to function as high-yield income streams. A model like this doesn’t primarily create new value, it arbitrages regulation. Time is up on that. Bring on the lawsuits.

No. 7

DPP Is Hawaiʻi’s Economic Chokepoint; Biggest Near Term Opportunity

Here’s the reframe. The Department of Planning and Permitting (DPP) is one of the most powerful economic levers in Hawaiʻi. (Yes, it is a bureaucratic nuisance, too. Two things can be true.) DPP governs time. And time, in construction and development, is money. Arguably, more valuable money than tourism dollars (it stays here), just not as sexy, and doesn’t have an HTA, to lobby for it.

DPP is a system under pressure that can either harden or reform this year. DPP has the chance to do the latter and, in doing so, set the tone for what structural change can look like across state and city government for the future.

What’s at stake is clear: without operational reform at DPP, Hawaiʻi will continue to price itself out of development and push costs higher. Delays and the inability to forecast accurately often provide industry operators too much uncertainty, and prices reflect this. Time can no longer be treated as if it has no economic cost. This is why the very public friction around DPP right now matters. DPP should lean in.

The numbers are not abstract. Estimates suggest DPP backlogs left behind more than $1 billion in direct construction costs (annually), with broader economic impacts easily 5x that amount, at $5 billion. In fact, DBEDT alone attributed $146 million to direct inflationary revenue missed tied to permitting delays. These dollars shrink projects, eliminate housing units, crush entrepreneurial dreams, and quietly transfer advantage to those who already own assets and can absorb cost overruns. This widens the wealth gap even more. First-time buyers, renters, small contractors, young families are paying the price. (I digress…)

DPP’s stated position that “revenue is not our mission” reveals a real leadership blind spot. Revenue is not the intent of a healthy permitting system, but it is the inevitable outcome. Pretending revenue is irrelevant is like an ER saying it’s only responsible for processing charts, not whether patients live. A functioning permitting system creates the throughput.

What’s often cited as DPP’s biggest weakness, the roughly 25% job vacancy rate, is actually its greatest opportunity now, if leadership gets this right. This is no longer about headcount and staffing up. The solution is identifying the institutional knowledge inside DPP and leveraging it through training and AI, so that staffing can be reduced, but be better compensated.

This is where AI matters. It cannot, cannot be layered onto broken processes. AI’s role is to remove administrative drag, routinize back-office work, and create visibility and forecasting so the people who actually know how to move permits can do that work at scale. Technology does not fix organizations; leadership does. Technology amplifies what leadership makes possible.

(One insight, more than a prediction, I’ve yet to meet a lawyer who really enjoys an operational turn-around job and is set up for success, especially one that requires energy, vision, and comes with unfavorable scrutiny. Years ago, the Head of DPP came in to solve one real problem that the FBI found, corruption. That’s over. Mission accomplished. DPP has evolved.)

If DPP gets this right, the impact extends far beyond permitting. The people who execute this turnaround will build a rare muscle in Hawaiʻi’s public sector: the experience of fixing something, BIG. That is institutional IP. And it’s transferable. Maybe what Hawaiʻi cannot get out of the private markets, can be built in the public sector.

Bottomline: A good chunk of tourism dollars leak out of the state; construction is one of the few industries where money reliably stays local. And yet we kneecap it with a permitting machine that treats delay as neutral. Accelerating construction is the most powerful economic intervention the city can make right now and accelerating permitting is how it happens. Turn-arounds are thankless until the job is done, that’s what the politicians are learning.

DPP is not a side story in Hawaiʻi’s economic future. It is the front line. DPP has a chance to prove the government can still be fixed. That is the scale of what’s at stake.

Let’s get it in 2026,

Sarah

…

P.S. If someone forwarded this to you, the best way to read or share it is the web version here.